Photo: Strong and Resilient (Kituwah Mound), by Dylan Rose

We humanimals have a complex and endearing habit of setting aside specific days to honor people, places and events. Consider the calendar: we currently use days of the week named by English speakers using Norse mythology borrowed from Romans. Sunday and Monday are named after celestial bodies, Sun and Moon; the other days are named after Norse gods: Tyrs’s Day, (W)odin’s Day, Thor’s Day and Frigg’s day. And lone Saturday originated from the Roman god Saturn, and is called Dies Saturni. And don’t even get me started on the months, with everything Roman: gods, planets and my personal favorite, February’s auspicious origin: named for a type of purification instrument known as a februa, which was used in the Lupercalia festival and intended to purify cities of bad omens at the end of the year.

What lies behind much of this are stories of intrigue and power, with various people trying to prove how important they were by naming something after themselves. Over time, this habit can wreak havoc on language and our entire reality.

In more recent times, we’ve taken to setting aside certain days to honor specific people, ideas and events, with the leader who appoints specialness of the day gaining favor. We currently have 11 officially recognized US National Holidays, ranging from President’s Day to Juneteenth. The origin stories of these days continue to tell of place, time and most predictably, the perspective and actions of those people who hold power within them. In the United States, these stories are often commercially driven, and steeped in political intrigue and colonialism. Which brings us to the story we are examining today, as we approach the second week in October.

The first mention of Columbus Day occurs October 12, 1792, organized by the Society of St. Tammany. Also known as the Columbian Order, this American political organization was founded in 1786 and heavily lobbied for the rise of Catholic Power in an increasingly protestant nation. They controlled the Democratic nominations and political patronage in Manhattan for over 100 years. And so, in a pro-Italian and pro-Catholic endeavor, the first Columbus Day was organized to commemorate the 300th anniversary of Columbus’ landing on this bountiful “new world.”

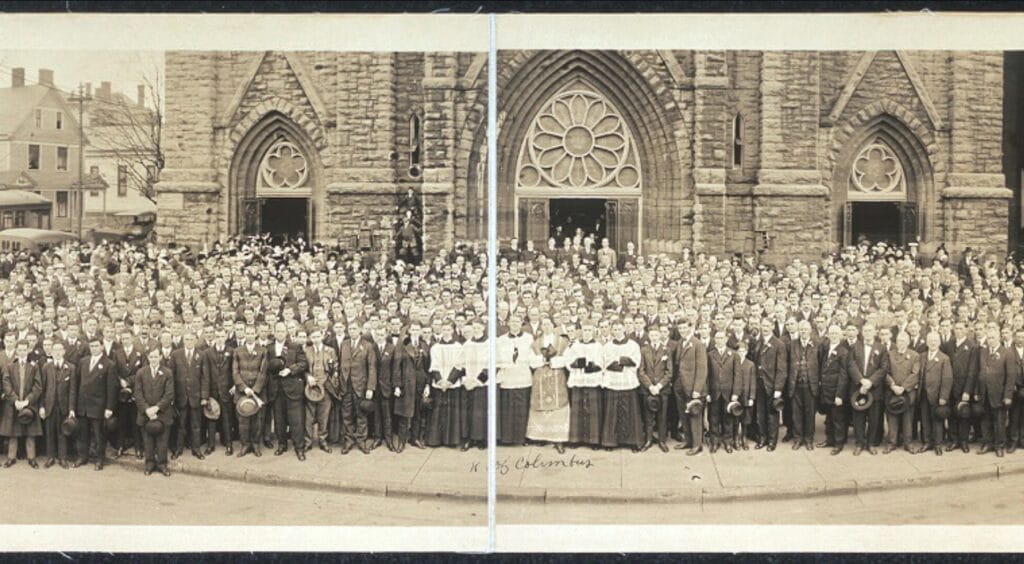

The 400th anniversary of that fateful contact inspired the first official Columbus Day holiday in the United States. Under heavy pressure by the Knights of Columbus (an international Roman Catholic fraternal benefit society) and in response to an anti-Italian motivated lynching of 11 Italian Americans in New Orleans in 1891, President Benjamin Harrison issued a proclamation in 1892. The day became popularly known by many as Italian Heritage Day, and was a point of pride as a celebratory day for many Italian immigrants–including my grandparents. As historical witnesses, we often observe patterns. Once again, pressure from political influences amidst racially motivated horrors were the main inspiration for the creation of the observance of this day. Why do we have such a tendency to bury atrocities in celebrations, to try and mask the brutal truth behind a holiday?

In 1977, the UN-sponsored International Conference on Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations in the Americas began to discuss replacing Columbus Day in the Americas with a celebration to be known as Indigenous Peoples Day. More and more Native groups worldwide were demanding that their rights be recognized and restored, and that the myth of Columbus’ “discovery” of the so-called Americas be debunked.

In July 1990, the First Continental Conference on 500 Years of Indian Resistance was held in Quito, Ecuador. Representatives of Indigenous People throughout the Americas agreed that they would mark 1992–the 500th anniversary of the first of the voyages of Christopher Columbus–as the year to officially promote “continental unity” and “liberation” and would retell the true history of that cataclysmic landing.

The plot thickens. I was an impressionable teen in high school in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1992, the 500th year anniversary of colonial impact. I remember when delegates from the Quito conference organized protests against the “Quincentennial Jubilee” that was being planned by the US Congress. The Jubilee was to include replicas of Columbus’s ships sailing under the Golden Gate Bridge and reenacting their “discovery” of America. Protesters stopped that reenactment from happening, and formed the Bay Area Indian Alliance and in turn, the “Resistance 500” task force. They promoted the idea that Columbus’s so-called discovery of inhabited lands and their subsequent European colonization had resulted in the genocide of thousands of indigenous people.

I remember feeling the passion of the people and the power in their solidarity; the need to stand up to things that were wrong. Another piece of tinder was laid upon the fire that was already kindled in my young heart for activism. And, Indigenous People’s Day continued to grow in popularity as a replacement for Columbus Day across what is now known as the US.

As if there wasn’t already enough story around this date, in 2022 on the 530th anniversary of the colonization of Turtle Island, President Biden signed not one–but two–official Presidential Proclamations in regards to October 10. He officially proclaimed it to be not only Columbus Day, but also Indigenous People’s Day–thereby becoming the only national holiday to celebrate two such opposing ideas on one calendar date.

Confusing, right? Yet the distinction is not arbitrary and points to the dualistic doublespeak that we tend to get from our government about important issues. Rather than own our history and make repairs, our leaders try to appease all sides, thereby continuing the harm by refusing to acknowledge the atrocities that came with Columbus to the original peoples of these lands.

Changing the name is not entirely void of impact, however. One of the most important issues that this name change addresses is visibility. Until we are actively engaging with the truth of colonization and its ongoing impacts on native populations, we are effectively continuing to sweep the repercussions of Columbus under the rug.

“I think it really recognizes that Indigenous People are still here,” said Alannah Hurley, executive director of United Tribes of Bristol Bay, a consortium of Indigenous communities in Southwest Alaska, and a Yup’ik fisherwoman. “We just have been struggling for so long for the vast majority of mainstream America and culture to recognize that—that we are not just in history books.”

She added, “We’re still fighting for our lands and our waters and our way of life. That visibility is huge because we have struggled for so long with being made invisible by mainstream society.”

With the rise of awareness and visibility comes recognizing the brutal realities that continue in the present day. For instance, Indigenous women, girls and two spirited people have up to 10x’s higher rates of violence and missing persons, many of which are never reported, let alone solved. The National Crime Information Center reports that in 2016 alone, there were 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls, though the US Department of Justice only logged 116 cases. Many believe the numbers are much higher and that due to poor reporting we may never know the true impact of this systematic erasure.

Maybe you’ve seen the red hand prints across the mouths of indigenous youths on social media, or red dresses hanging from trees, windows and doorways; but do you know what they signify (featured image above)? Although May 5 is the official day set aside to honor MMIW (Missing or Murdered Indigenous Women), it feels important to mention it in the context of the story of Indigenous Peoples Day. Indigenous People continue to navigate the impacts of colonialism every day. Their ancestral lands, cultural traditions, native foods and language have all been systematically stripped away in an effort to erase them.

And to erase our white guilt; but the only way out is through.

European Americans must now endure the pains of laboring through the genocide that came along with us to the shores of these lands that fateful day in 1492. Now, 531 years later, we must collectively work through our history and find ways to acknowledge the atrocities of our ancestral legacy, not just with words; but with action. We can no longer be immobilized by our shame and fear: fear of doing or saying it wrong, not knowing enough, not being ready. It is time to be tenderly vulnerable and brave, to put ourselves “out there” for the sake of others and for our own peace of mind; to listen and learn with humbleness and dedication. For until we make amends for and learn from our history, we will never be at peace in our own selves.

About the Author

Marissa Percoco is the Executive Director of the Firefly Gathering. Having grown up in the concrete labyrinth of the San Francisco bay Area, Marissa escaped to the wilds in college and has never looked back. She is a naturalist by heart, and is deeply rooted in the Earthskills movement, anti-oppression work, her garden, and the old Appalachian soil.