There are so many special ways to look at the Southern Appalachians–through the lens of birds, their migratory routes, their song lines that raise the sun into the sky each morning, and lower the sun each evening. Or rocks, those sleeping dragons whose ridgelines snake around our region. In excitement for the upcoming workshop, Our Magnificent Trees: Identification, Uses, Folklore, and More with Luke Cannon on November 5th, I’d like to introduce another lens through which to experience our bioregion: Ecotones.

The word rolls off the tongue–ecotone. Say it with me. Ecotone. There’s something melodic about it, like it’s part of a musical composition; the ecotone of a song. In ecosystems, the ecotone is indeed like a musical notation–indicating where the landscape’s song changes from one ecosystem to the next.

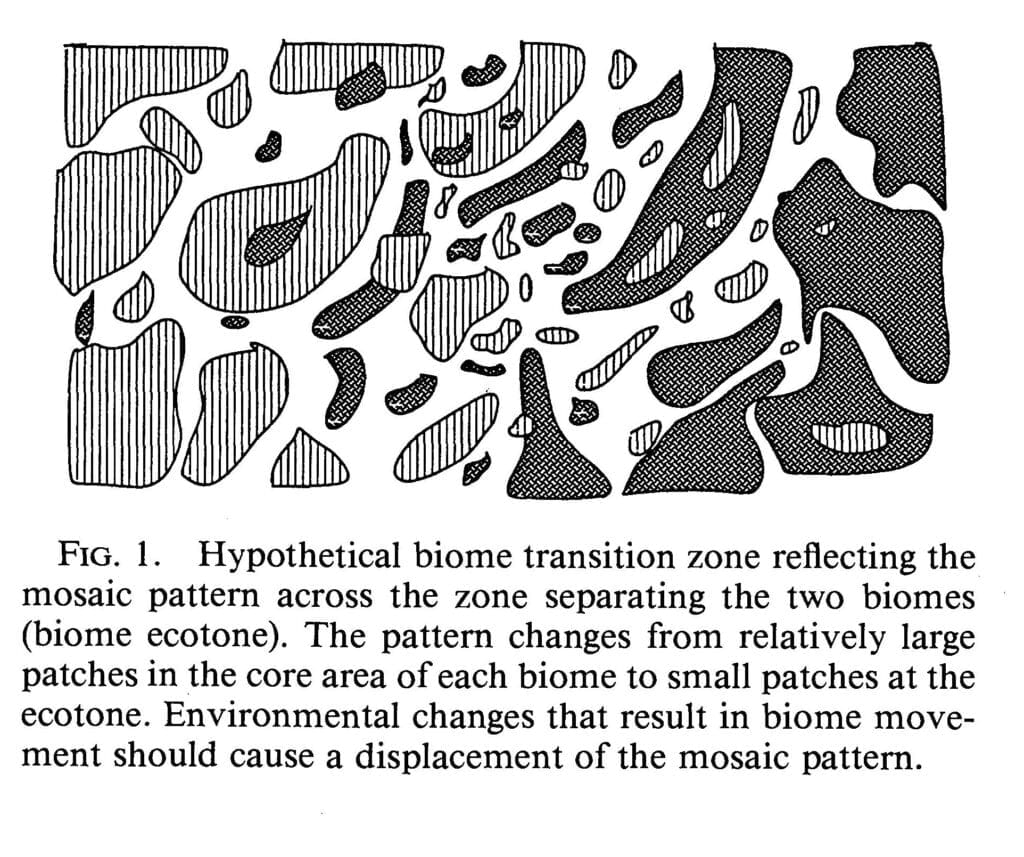

An ecotone is that area of in-betweens, where the members of each different ecosystem overlap, share the same habitat, morph and shapeshift. It’s where species get to do some intense learning, as they learn the songs of different genetic lineages, they learn the dance of cousin creatures, exchanging plastids and genes, songs and instruments.

The ecotones are the meeting places between habitat cultures. Red spruce forest meets the sphagnum bog. Upland Birch forests meet Oak woodlands. Granite dome system meets Carolina Hemlock groves. Cove Hardwood forest meets White Pine groves. Eastern Hemlock forests meet rushing riparian corridors.

Firefly Gathering is like a giant ecotone, too. Where wool artists link up with blacksmiths, and naturalists learn social justice pedagogy. But ecotones aren’t just about closeness of members; they can also be about a meeting between times: ancient futures, sticky presents, and decomposing modernities.

Where do you find an ecotone? Luckily, ecotones are everywhere in the Southern Appalachians due to the incredible elevational gradients that yielded it to be an Ice Age refugium. When you stand on the edge of a spruce fir forest that is shifting into a northern hardwood forest of yellow birches, you are in an ecotone. When you clamber from the side of a river into a mixed oak forest, you traverse an ecotone.

We can usually feel when we’re in an ecotone: time seems to unfold; boundaries between worlds seem to shiver; lines between self and other blur.

In our forested ecotones, there are rarely any lines that designate the distinction, it’s more that one ecosystem finds itself near its limits, as another ecosystem finds itself at its beginnings.

These liminal places are where the most interesting things can occur. It’s like a sandbox where adaptation to tougher climates, challenging hydrology, or different microbial communities can be tried out, worked through, experimented within.

From a genetic perspective, it’s those members of an ecosystem community who live on the margins–in the ecotones–who are doing the work creating genetic and behavioral adaptations to future climate change, habitat change, water regime change. It’s these struggling members who are feeding what they learn, through their genes and behaviors, back to the center of their communities.

As are we who comprise the Firefly community. So many of us are living on the margins of modernity, eeking out a living, striving to create healthier ways of relating to each other and ourselves; peeling back any purist identities to recognize our perpetuation of settler-colonialistic behaviors that dominate and destroy, while carefully planting seeds that might repair and rebalance.

We are learning how to navigate these margins because we know the centers of the dominant cultures are rotten at their core. Everything we’re learning might feel like it drops into the void–but each little seed is worth more than we know. We know that the ecotone is the most diverse part of the forest, where growth and adaptability emerge. This is why Firefly is so committed to building equity and diversity into our organization and community; learning from nature, we know that there is evolutionary strength in diversity.

Like ecotones, what we are learning is feeding back to the center of humanity, for ancient futures, for the future generations, for the present generations. Cultures where gender norms are diverse, like trees. Where trans-rights are equivalent to the biological rights of caterpillars and butterflies to transform and change. Where Indigenous rights are as inherent and foundational as the bedrock of these mountains. Where the rights of the global majority are as unquestionable as the Earth. Where patriarchy and white supremacy dissolves within the forms that hold them, like a Coprinus mushroom decomposing itself into inky relinquishment. Where human centrism moves to the side of the biospheric stage. Where the rights of nature rip through the doctrines of discovery.

Ecotones. Take a breath next time you walk through one.

See what dreams and thoughts come alive–for you might just find that your consciousness shifts as you move from one ecosystem to the other.

To learn about the Magnificent Trees in the ecosystems of the Southern Appalachians, whose songs shift and change along the ecotones, join Luke Cannon for one of his imagination-expanding, tree-connecting walks this November.

About the Author

Nastassja Noell (she/they) is a lichenologist who struggles to stay within the fenced pastures of science. Their creative writing and art has been featured in Dark Mountain Project, has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and they are a recipient of the United Plant Savers’ Deep Ecology Artists Fellowship. She has led lichen biodiversity research projects throughout the Americas, co-authored the book Delmarva Lichens (Torrey Botanical Press), and her writing has appeared in scientific journals as well as Radical Mycology, Patagon Journal, and NW Travel. Nastassja works for the earthskills school Firefly Gathering, and lives in the Southern Appalachians on the ancestral lands of the An-igiduwagi (Cherokee) People. You can find more about her and her work on her website beinglichen.org or Instagram: @beinglichen.